My Issues with the Modern Menswear Scene

Telling my story within the menswear scene in NYC over the last 12 years, and identifying things that are irking me presently.

I’ve only posted photos and interviews here, but some of my favorite things I’ve read on this site are personal essays, however scholarly or introspective.

I used to write for catharsis. It came easily to me. I’d type long essays in college in a trance, like my thoughts were coming from elsewhere. Over time, a phone-induced dopamine addiction broke my brain and attention span. I stopped writing for joy. I barely read books like I used to. So, in an attempt to reclaim my passion for writing, I am going to do my best to check in here more often with essays like this one.

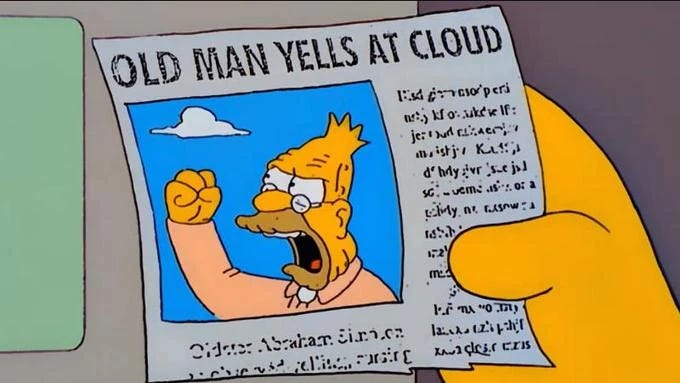

Because most of my output online has been effusive, you might not know that I am also a Schedule 1 hater. And something that is bothering me presently is some of the dialogue around menswear.

In 2011, when I was surfing Tumblr, playing Fallout 3 and watching Mad Men between freshman year college courses, I had the extremely corny but genuine thought that it would be cool if the average man cared about how he looked in public. Thankfully the term metrosexual was nearly eradicated, but hipster was having its moment, and though a hipster was a fairly tangible thing—of which there were many in my literature classes at Eugene Lang—this term was often ascribed to me. I was wearing The Tie Bar ties with J.Crew shirts and vintage blazers to class. My pants were perfectly slim. Whatever you wanted to call me, I had it figured out, and hopefully, regular guys would one day catch up.

But quickly, the reach of menswear expanded. Fashion became more popular. Being bestowed with the #Menswear tag on Tumblr took your posts to new, previously unseen heights. Men’s jeans got tighter. Suddenly, guys who were calling me a “homo” in my teen years finally cared about their own style. Here, my naivety became clear. I wished (and still wish) they stopped caring again.

When I really started to enmesh myself within the NYC menswear scene, the look was double monk strap shoes, popover shirts, pants with two-inch cuffs, and unstructured Italian blazers from brands like L.B.M. 1911, Isaia, or Boglioli. I could barely afford the cheapest versions of these things on a Billabong paycheck, but slowly I found ways to assimilate. I discovered most of my new friends—people I had first followed and became a fan of through Tumblr—had other interests besides clothing, many of which aligned with my own.

Well before the acronym that makes me seethe “iykyk” entered public lexicon, I thought no one dressed like us; you had to know what we had on to really get it. Of course, this was also naivety, because brother, I had a god damn costume on half the time. Sometimes I looked great. A lot of times I looked stuffy. I was trying to keep up and fit in. But a lot of what I learned about myself and about style during this period was invaluable.

In 2013, I heard a store called Carson Street Clothiers was going to open in SoHo. The menswear community was aflutter. I wanted in. After acquiring co-founder Brian Trunzo’s email, of Nice Try Bro fame, I politely… consistently contacted him for a job. He will tell you to this day that I annoyed the shit out of him. I might have asked him, already knowing the answer but wanting to show him I was in on the thing, if his L.B.M. blazer was “Lubiam.” After a while, probably out of pity, he offered me an unpaid internship to which I responded that I needed a paid job and would do literally anything to keep his business running smoothly. I’d worked retail. I’d managed Billabong Herald Square for Christ’s sake. I was graduating college within a year with a literature degree, so I had physical proof I knew how to read dense texts; a skill needed to deal with the customer service account of a men’s store that sells tailoring. I could write; tons and tons of product copy, and responses to those customer service emails. I could even take photos. My persistence paid off. After interviewing with him, co-founder Matthew Breen, and the two shop managers, Patrick Doss and Chris Rucker, I had finally gotten my dream job.

Initially, I worked retail on the floor, learning about all of the great brands on our roster from all of my adopted older brothers, and even from folks at the brands themselves. I learned how to pin garments to be tailored to better fit a multitude of body types. I learned what colors and fabrics worked for different folks. I learned even more about my own style through trial and error. I thought there couldn’t be a cooler place to work on the planet, and for the time the store was open, that was probably true.

They brought me to the European Fashion Week circuit on their buy trips to document the journey. I’d take street style photos for our blog, but I’d also take pictures in the showrooms or at fashion shows that we’d attend. I’d even interview designers. I sat down with Alexandre Mattuisi before AMI became the juggernaut it is today. And Umit Benan, and Massimo Alba. I’d photographed Yasuto Kamoshita after sharing drinks with him at a rooftop happy hour in Florence. I was eager to soak up all of the expertise I could. I will forever be grateful to Brian and Matt for the doors they helped me open.

My point in recounting all of this is to show I did the work. I learned about this industry in all of the facets available to me and then some. I made meaningful connections through networking—and not the kind of empty bullshit I see and feel in NYC these days at menswear events. There is an art to meeting new people—to making them feel heard, to telling your own story, to getting your foot in the door. It’s okay to forget a name, but pretending to forget a face, or worse yet, forgetting a face purposely because you think you’re above someone, is shameful. Of course, honest accidents can occur.

Taking shortcuts, acting entitled, and using people can only get you so far. Dressing appropriately for an event is always safer than wearing all of your rarest and newest (importantly, not yet battle tested) garments. My philosophy, trite and Esty-poster-bound thought it may be, has always been to work hard and be nice to everyone I meet. I will be entering my sixth year freelancing this upcoming January, and I am honored to have amassed the clients and portfolio of work I have thus far.

During my time at Carson Street between 2013 and 2016, Instagram rose in popularity. Today it is a completely different app than what it was originally. That’s obvious to the naked eye. To dig in a bit though, I have roughly 21,700 followers and my posts are getting the least engagement I’ve ever experienced. Photos I am deeply proud of will get 60-70 likes, viewed by 3000-5000 people—that’s bad. It’s difficult to resist the urge to apply judgement to my work when Instagram makes my reach so easily quantifiable.

And yet I know what I could do to get more followers and engagement. I could pay for a verified account. I could start making Reels. But that would be forcing it. I refuse to put my name on something inauthentic. Of the 160 some odd Five Fits With installments I have published, I have only deviated from my formula for a handful, and for those I’d blame clever PR folks for doing their job well and working their sorcery on me.

The handsome menswear influencers of today have hundreds of thousands of followers. They are broadcasting videos from their spacious, well-furnished apartments, knickknacks and totems zhuzhed just so in the background. It is hard not to be drawn in by their siren song. But, some are preaching absolute malarkey about personal style. They are telling their followers about trends to look out for and tap in to. A lot of them simply like clothes and how they make them feel, and that’s great. That’s the best reason to enjoy clothing and the community around it. But they are speaking as authorities without having done the foundational work to become authorities.

At an event I was photographing earlier this year, I wore a James Coward Belgian linen trucker jacket underneath my outerwear. A prominent menswear influencer complimented me on it. He fumbled around a bit for the words to describe it, but finally said to me, “So, it’s… like… a denim jacket?” I responded that, yes, it’s shaped like a common trucker jacket, but something about the proportions led me to believe it’s taking cues from an early 1900’s model. I watched his eyes glaze over when I started to get too granular for his attention span.

Look, I’m a dick, and he meant well. But this brief moment stuck with me throughout this year. It illustrates my main gripe. Guys in this industry used to care about history and the reasons pieces became iconic. They cared about the legacy of a brand and the stories those brands were trying to tell. It wasn’t about commodifying knowledge or doling unprompted expertise to the masses. We were sharing in something inherently nerdy, and sharing it with like-minded people who found this subculture to be fun and unique. We weren’t trying to become influencers or consultants.

Modern influencers are being paid by brands to tell their followers their products are their favorites, even when they know the product is poorly made or does not suit their tastes. It’s important to be skeptical of a writer’s, or creator’s, relationship to a brand before digesting the information they are divulging, most of all when they are being paid to do so. Those brands are attempting to cash in on what’s next, because they are directionless. They have no narrative. They are not helmed by artists with statements to make. They are trying to gamify an industry that once proved itself driven by creativity first.

There is this uncanny uniformity in the perceived individuality I see around New York City. The look du jour for the normal-guy-in-the-know seems to be baggy jeans, a cropped graphic t-shirt, a trucker hat, and a mustache. And that existed when I was coming up in NYC, wearing my own costume and looking just like my friends and colleagues. You can’t get a grip on your own style without copying someone somewhere along the way. You will be influenced. Style is about knowing just as much about what doesn’t work for you as what does. We all have different bodies, skin tones, hair textures, and bank accounts. The day you truly stop comparing yourself to others is the day you unfetter yourself from the shackles of defining personal style.

I went to a dinner recently and one of my friends confidently declared, “Red shirts are next-up!” To which another man at the table replied, “And cobalt, too!” But as I enter my 34th year on this planet and approach Unc-hood, the concept of next-up exhausts me. Say red shirts really are next-up. You go and buy one, you wear it to impress people whose opinions don’t matter, and then what? You sell it in a year and buy the next thing that’s next-up?

Don’t get me wrong. I have fallen (and will again fall) into this trap. It’s impossible not to. I bought Rick Owens and Raf Simons when I worked at Grailed back in 2016 because I wanted to impress my peers. I wanted to signal to people in the fashion industry that I knew as much as they did. I think some avant-garde stuff looked decent on me. I loved the Rick Owens pieces I had specifically—a few pairs of Pod shorts, Creatch cargos, Island Dunks (which are still a prized possession), Detroit waxed denim (my pant of choice to get obliterated and dance on tables at Kinfolk to Travis Scott and Migos in)—but they weren’t really me. I didn’t have the bank account for high fashion. I still don’t.

Speaking of math, this menswear obsession with numbered lists is confounding. We can thank listicle culture for its lasting impact on our dialogue and on fashion journalism. I have friends who make their bread and butter on this stuff. No shame. I am not knocking the hustle. I understand the impulse to find a cheat code to dressing well, especially when an authority is dishing out the advice. But you cannot distill the weird, messy, personal journey that is finding one’s style this easily. It is not an algebra equation that can be solved with integers.

Proportion is key. What works for one guy probably won’t work for you. There is no single prescription that will unlock looking good because looking good simply means you are comfortable in your clothing and in your skin. That might sound obvious, but I see enough evidence of the contrary every fucking day. I’ve had conversations with some of the best dressed folks in the world about style, on and off the record, and the word brought up the most is comfort. So, find what makes you comfortable. That’s when you look and feel most attractive.

For posterity, I’ll end this somewhat ironically with a list, though mine is free of numerals. It’s simply presented here for you to (hopefully) discover some dope stuff that I’m currently loving in menswear: new arrivals at my all-time favorite shop, C’H’C’M, James Coward, Shop Overdye, Reigning Champ sweats,

’s unflinching Instagram presence, Cale Darrell’s (formerly Shop Good Form) brand and vintage curation, Neighbour, Arpenteur, and ’s Substack, That Dusty Heat.

So well done

Amen, man. Reading some of those names in the piece really took me back to the old days, too…